Babich, Progress in Science and Art

Borderless Philosophy 8 (2025): 1-31.

1. Introduction: Progress and Decline, Evolution and the Primitive

The idea of “decadent art” is well-known from its use against cultural elements often associated with Jewish artists during the Nazi era.1 But, as Paul Feyerabend (1924- 1994) points out, the idea of Verfall was well-established in the Renaissance recovery of classical ideals, revitalizing Hellenic art against supposed Roman decay, degradation, or “barbarization,”2 the same ideals Feyerabend also reads in connection with the discovery of perspective along with the social elevation or transformed status of the artist.

The constellation is essential for an understanding both of Feyerabend’s interest in art, including Dadaism, Avantgarde, modern and abstract art as well as his interest in Brecht.3 Where things become complicated will be in connection with what was crucial for Feyerabend’s philosophy of science in connection with the idea of progress as such, as if toward just one goal, one truth, one culture. This Feyerabend would contest—as did Friedrich Nietzsche4 —in his thinking on science. Today we are closer to beginning to understand Feyerabend’s insistence on “epistemological pluralism” if this notion often continues for many thinkers to be compatible with an evolutionary ideal of truth towards which “science,” so the conviction, inexorably tends. This ideal of progress Feyerabend challenged quite for the sake of understanding science throughout his work especially patent in Against Method. This contestation permits him to reflect on the point of Ivan Illich’s edifying gloss of Hugh of St Victor’s Didascalicon—“Never look down on anything” (Illich, 1993: p. 29)5 —as Feyerabend emphasizes in the title of the third chapter of Against Method: “There is no idea, however ancient and absurd, that is not capable of improving our knowledge” (Feyerabend, 1975/1988/1993: p. 5—see also pp. 33-34).

In Feyerabend’s posthumous, Quantum Theory and Our View of the World, in a Heinleinesque section entitled, “Humans as Aliens in a Strange World,” Feyerabend explains that the Gnostic movement, for example, occurred at a time of uncertainty when humans seemed subjected to irrational political and cosmic forces and when help seemed far away. Here are humans “as they really are,“ i.e., “their souls are imprisoned in bodies and the bodies in turn are imprisoned in a material cosmos. This double imprisonment, effected by low-level demons, prevents humans from discovering the truth: the more information they possess about the material world, the more they get involved in it, the less they know. Revelation frees them from their predicament and gives them genuine knowledge“ (Feyerabend, 1999: p. 168).

Teasing his former colleague, Joe Agassi, for his limitations as a reader in Science and Society, concerning “The Strange Case of Astrology,” Feyerabend contends that today’s scientists and, by extension, philosophers of science, have little hesitation when it comes to denouncing things about which they are utterly ignorant, knowing only that it cannot be true to which habitus Feyerabend opposes —the example is meant to be extreme — the Church and the Inquisition, analyzing the exigence of the logical argument and case structure of the Malleus Maleficarum,6 but also inasmuch as, as Nietzsche also observed, the notion of a singular and ideal truth has analogies with traditional theology (see Babich, 2014).

Feyerabend’s Wissenschaft als Kunst [Science as Art — this should not be translated as “Science as an Art”] (Feyerabend, 1984), must be read in the context of a debate on the sheer idea of progress per se. Feyerabend uses progress in art in analogy with the ideal of scientific progress as these themes feature in his posthumously published (but contributed, so Bob Cohen told me in conversation, in Feyerabend’s lifetime to Cohen’s Festschrift), under the title of “Art as a Product of Nature as a Work of Art” (Feyerabend, 1995), an essay reflecting Feyerabend’s protracted interest in what German speaking scholars call Naturphilosophie, a tradition which attracted both Feyerabend’s mentor/nemesis, Karl Popper and his friend, the physicist, Erwin Schrödinger.

It goes without saying that arguments contra non-received themes also support excluding knowledge traditions, including certain styles of philosophical approaches to philosophy as to the philosophy of science and history along with anthropology and sociology of science in addition to excluding aention to whole historical epochs, this Pierre Duhem (among others but Duhem at remarkable length)7 sought to challenge in medieval cosmology and also, as we are slowly learning to do with respect to different traditions of ancient science, Hellenistic, Chinese, Indian, etc., and, as Feyerabend argued at length, stone age culture as well.8

2. Wissenschaft als Kunst/Science as Art

Introducing his 1981 inaugural lecture in Zrich: “Wissenschaft als Kunst” Feyerabend compared the concept of scientific “progress” with “progress” in art (Feyerabend, 1984: p. 7).9 The nuanced opposition to the idea of (simple) progress is the heart of Against Method and there are several versions of Feyerabend’s thinking on progress in science.10 In art, Feyerabend argues contra the Renaissance theory of barbaric external depredations or internal decay [Verfall] that also found expression in Nazi arguments against Avant Garde and modern art as “degenerate” [Entartung].

In addition to clarifying Emmanuel Löwy’s (1857-1938) discussion of the complex advances of archaic style in Greek art, Feyerabend foregrounds Aloïs Riegl (1858-1905),11 the art theorist who revolutionized art historical research quite thematically as a “science”12 Kunstwissenschaft, qua science, as Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), if he does not typically tend to be read in this fashion, had likewise highlighted as “aesthetic science [ästhetische Wissenschaft]” in his first book on The Birth of Tragedy out of the Spirit of Music, as Nietzsche himself draws on his own inaugural lecture on the “Homer problem” that would also engage Feyerabend.13 Nietzsche maintained that in his first book he put science as such on the very Kantian “path of a science,” raising the question of science as “a problem, as question-worthy.”14

Claiming to be the first to have posed this question and the reflexive significance of the indispensability of the ‘ground of art [Boden der Kunst]’ inasmuch as “the problem of science cannot be cognized on the ground of science [denn das Problem der Wissenschaft kann nicht auf den Boden der Wissenschaft erkannt werden]” (Nietzsche, 1980: vol. 1, p. 13), Nietzsche had claimed a revolutionary turn while also, thus the irrecusable connection with the question of style, making the scientific case that it was style that exemplified the ‘science’ of his own scientific field of ancient Greek philology. In other words, as Nietzsche explained in his Basel lecture, the expert designation—this is technically what is called the “Homer question”—of “Homer as composer of the Iliad and the Odyssey is no historical tradition but an aesthetic judgment” (Nietzsche, 1869/1994: vol. 5, p. 299). Feyerabend cites Nietzsche on “truth and lie” along with Nietzsche’s Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks and it is important to note that in both texts Nietzsche highlights “style.”

If Nietzsche’s thinking on truth and lie is prototypically incendiary—classical “dynamite” for standard philosophical thinking on science—Henri Zerner argues that in his foundational contributions to art history, Aloïs Riegl’s innovations also undermined all the fundamental convictions of traditional art history. These convictions have by no means disappeared today. They are not, it is true, very comfortably held, but neither have they been replaced by what one might call a new paradigm (Zerner, 1976: p. 179).

What drew Feyerabend’s attention in his analogy, “Wissenschaft als Kunst [Science as Art]” was Riegl’s opposition to a patent presumption of aesthetic “progress,” whereby historically prior traditions are esteemed as less advanced, accomplished or competent than subsequent traditions. This Feyerabend recalls as the standard assumption of Vasari’s account of the evolution of Renaissance art (Feyerabend, 1999: pp. 89-90). It is this same assumption that drives the classification (the language) of assessing art of certain historical periods as “decadent” (see, broadly, Kuspit, 1994, 2000; and Kaye, 2020) with notorious consequences in the case of Nazi aesthetics, as already noted at the outset, but which led, here to use Jás Elsner’s terms, to characterizing “late antiquity as the fag-end and dust-bin of a dying aesthetic” (Elsner, 2021). It was this valuative ideal of the progress of art that Riegl refused. Hence where Vasari articulated a progressive schema in the “evolution” of art, Riegl’s account of the history of art articulated a properly scientific, comparative historical analysis beginning with the art of antiquity in Egypt, Greece, Rome, Byzantine, Islamic, Germanic, showing art in tension with or else “improving on nature” in various ways and subject to contextual as opposed to absolute acme and decline (Riegl, 2004).

Summary glosses of Riegl’s contributions to scholarly, scientific thinking on the history of art highlight his concept of Kunstwollen (‘wollen’ is difficult to translate, ergo hermeneutically “elusive,” here again to use Zerner’s words, “because it seems to vary with its context” [Zerner, 1976: p. 180). Contemporary scholars find themselves challenged to situate Riegl, as they claim his “limited citation of sources” (Gunser, 2005: p. 453), but such a claim typically frees scholars to reconstruct these, thus Rebeka Vidrih positions Riegl between von Humboldt’s “Bildung durch Wissenschaft“ and Dilthey’s conception of the Geisteswissenschaften (Vidrih, 2023 : p. 1), and so on. The distinction is complicated for Feyerabend, who never failed to point out that rigorously or “strictly speaking all sciences are Geisteswissenschaften” (Feyerabend, 1981: p. 12).

3. “Brunelleschi and the Invention of Perspective”

In The Conquest of Abundance, Feyerabend quotes Antonio di Tuccio Manetti’s speculative aesthetic analysis of the upper portion of the painting in which, according to Manetti, Brunelleschi had

placed burnished silver [in the painting] so that the actual air and the sky might be reflected in it, and so the clouds, that one sees reflected in the silver, are moved by the wind when it blows.15

This account has been called into question by the sculptor, Nigel Konstam (1932-2022), in his experimental (re-)construction, arguing that the mirror was a device, that is to say, expressly what Feyerabend called an “artifact” in his argument.

Konstam maintains there were two mirrors as the original painting, which has been lost for centuries, containing a sketched and painted substrate of silver quite as opposed to featuring, according to Manetti’s reasoning (which not based on observation) that the original painting included a mirror inlay of silver in order to provide a dynamic reflection of passing clouds in the sky.16 The historian of renaissance art, Samuel Y. Edgerton (1926-2021) observes that a subsequently added inlay, although common in other applications, used by an artist for such a purpose would have been a singular innovation: “as far as I know, no other artist before or aſter him had ever thought to do” (Edgerton, 2025).

According to Konstam’s video demonstration of his experimental reconstruction, Brunelleschi would have traced points for perspective projections for the painting directly on the silver mirror itself, thereby leaving unpainted what for Manetti appeared as sky, featuring passing clouds or whatever else is reflected (cf. Tsuji, 1990).

Konstam’s account is illuminating in several respects.

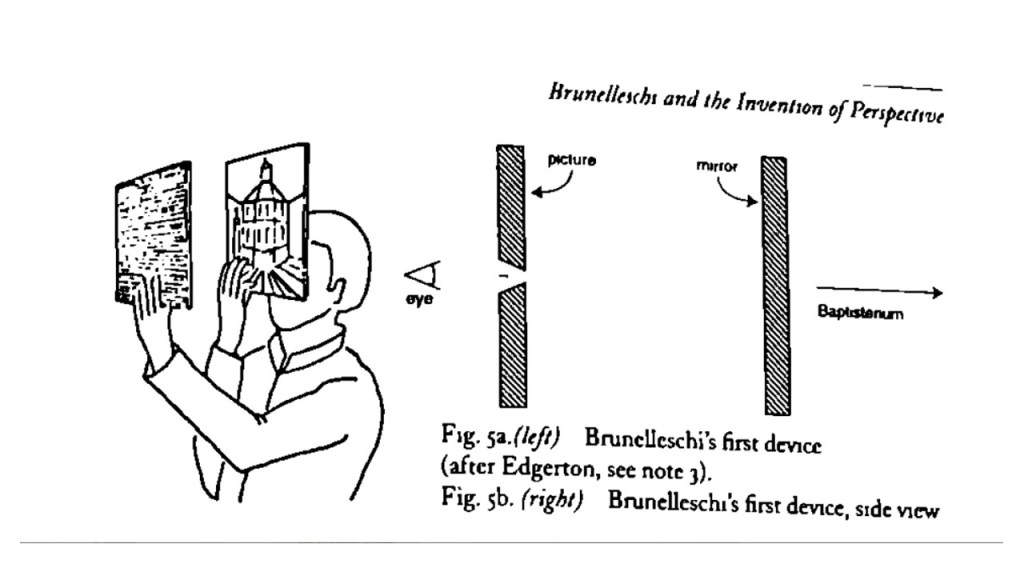

In Space-Perception and the Philosophy of Science, Patrick Heelan had emphasized that conventional or “artificial perspective” (i.e., classical perspective)17 was designed to reflect “the way Renaissance artists organized space predominantly according to the rules of mathematical perspective” (Heelan, 1983: p. 101). This is the same point Feyerabend makes at the outset, citing Richard Krautheimer and featuring Edgerton’s illustration of Brunelleschi’s engineer-artisanal “experiment” with respect to linear perspective (see Fig. 2 below).18

For Edgerton and Feyerabend (and not less for Konstam’s artisanal reconstruction), the instruments or artifacts are key. But Edgerton emphasizes that everything used in Brunelleschi’s “experiment”—the mirrors, the panel, but also the original sketches, drafts, paintings made, have been lost—as well as the experimental practice, crucial to which, as Edgerton echoes Filarete, pointing out that Filarete was likely, because Manetti, too young at the time, would/could not have been a witness, and was thus “looking in a mirror” (Egderton, 1975: p. 134).

Therefore, reference to the perspective frame illustrated in Dürer’s treatise on measurement, Underweysung der Messung19 —which, it is worth noting, include the perspective points Konstam emphasizes, along with the use of mirrors and a fixed optic (see Fig. 3 below)—supported the claim that

the camera, like mathematical perspective, was developed to serve a pictorial vision that already defined the World to be of a certain kind and to assist painters to express this. (Heelan, 1983: p. 102)

In addition to his focus on Brunelleschi’s experimental set up or Gestell, Feyerabend argues against the Vasarian ideal of verisimilar artistic evolution or progress and to this end he draws on Riegl.20

(Wikimedia Commons)

At issue is the concept of “progress,”21 including social progress relating to the rank or banausic standing of the artist. For Hans-Georg Gadamer, who cites both Karl Popper and Martin Heidegger, what is crucial is “the discovery of new questions” in the “emergence of a scientific problem” (Gadamer, 1998: p. 25). Gadamer argues that both Mill and Dilthey presuppose what may be regarded as “the objectivity of method” (Gadamer, 1998: p. 30). “Methodos,” for Gadamer, “always means the whole business of working with a certain domain of questions and problems” (Gadamer, 1998: p. 30). In this sense, the history of philosophy is not a history of “stable problems” (Gadamer, 1998: p. 28). For his own part, Feyerabend makes this claim with respect to the history of science. Thereby instability is ineliminable: “we are historical creatures,” an insight differently articulated in Riegl’s art-science: for Gadamer, “we are always on the inside of the history we are striving to comprehend” (Gadamer, 1998: p. 28).

Full pdf, including the following sections and complete reference list available here.

Notes

- See, in general, although there are other studies—some cited in note 20 below—the essays collected in (Peters, 2014). ↩︎

- See, for example, (Peirano, 2010). Such claims, and Nietzsche also discusses this, are related to efforts at cultural appropriation; see (Miles, 2015), as well as, also relevant for Feyerabend’s reference to Vasari (De Angelis, 2008). ↩︎

- Val Dusek argues that this illuminates Feyerabend’s dialogue with Lakatos, see (Dusek, 1999). Dusek’s reading would have benefitted from further context, literature, references, etc. and should certainly be supplemented with Matteo Motterlini’s enlightening publication of their letters: see (Motterlini, 1999). See also, for further references and discussion (Babich, 2024). ↩︎

- See for discussion, (Babich, 1994/1996/2020). ↩︎

- Illich’s gloss is meant as a comment on Hugh of St Victor’s Parvis imbutas tentabis grandia tutus which, Illich tells us Jerome Taylor translates more soberly as “Once grounded in things small, you may safely strive for all.“ ↩︎

- For the reference to Inquisition (in the context of his argument re arguments contra astrology), see (Feyerabend, 1978: p. 92), and with reference to Gnosticism, noted above, Feyerabend sets the thought experiment: “Can we infer that the final product, i.e., nature as described by our scientists, is also an artifact, that nonscientific artisans might give us a different nature and that we therefore have a choice, and are not imprisoned, as the Gnostics thought they were, in a world we have not made?” in (Feyerabend, 1999: p. 138). ↩︎

- See, in ten volumes (Duhem, 1913-1959). For a discussion, see, including reference to Feyerabend along with a discussion of Mach, (Babich, 1993/2003: pp. 187-194). ↩︎

- See the first chapter of Feyerabend’s Naturphilosophie (Feyerabend, 2009/2018). To understand Feyerabend’s approach, it is salutary to compare, and note the subtitle, of (Meyer-Abich, 1997), because Meyer-Abich underlines ecological and political issues, not unlike if more ecologically focused than Feyerabend. ↩︎

- Cf. (Feyerabend, 1986), and, again, (Feyerabend, 1995), a version of which also appears, among other loci, as a key chapter in his posthumous Conquest of Abundance (Feyerabend, 1999). ↩︎

- See for a now classic objection—and strikingly but not exceptionally limited reading of Feyerabend— in (Theocharis and Psimopoulos, 1987). For a reflection on philosophy of science per se, see (Stuart, 2021). And, for a comparison of Feyerabend and Popper, see (Tambolo, 2015). ↩︎

- To wit: Eine Diskussion der Rieglschen Kunsheorie verbunden mit dem Versuch, sie auf die Wissenschaften anzuwenden. See for a discussion of Riegl and Löwy, (Delarue, 2014) and, on Löwy, in English Alice A. Donohue’s discussion of Löwy’s rendering of nature in archaic Greek art in (Donahue, 2011), which she reads with the same reference to the Gombrich Feyerabend tells us he consults, reminding us that Gombrich was Löwy‘s student, highlighting, as this is also crucial for Feyerabend, Löwy’s discussion of the representation of space, although her reading of Löwy’s discussion of Homeric narrative might have benefitted from Feyerabend’s paratactic discussion. ↩︎

- Cf., focusing on Aby Warburg and Ernst Gombrich (Vidrih, 2023) and see (Cordileone, 2014), and, for the relevance of the icon (Ionescu, 2013). ↩︎

- See, including a reference to Darwin, (Babich, 2010). ↩︎

- Nietzsche, 1980: vol. 1, p. 13; and for discussion, see Babich, 2009. ↩︎

- Manetti, in The Life of Filippo Brunelleschi, ca. 1480, quoted in Holt, 1981: p. 171. In a note, Feyerabend tells us that he changes the translation, using “technical language where the text has none” (Feyerabend, 1981: p. 95). ↩︎

- See (Konstam, 2025). I invoke some of Konstam’s material argumentation with respect to technique in (Babich, 2007), referring to (Konstam and Hoffmann, 2004). ↩︎

- Embedded in this, as Erwin Panofsky argues, are two collimated conceptions of experimental perspective, “the perspectiva pingendi [painter’s perspective] or perspectiva artificialis [artificial perspective]” both of which were dependent on optics and frames and the artist’s specific staging (think of Dürer’s famous depiction of perspective, Fig. 3) and hence quite literally the child of optical theory and artistic practice-optical theory providing, as it were, the idea of the piramide visiva [the visual pyramid], artistic practice, as it had developed from the end of the thirteenth century, providing the idea of intersegazione [a plane intersection of the visual pyramid]” (Panofsky, 1960: p. 139). ↩︎

- (Feyerabend, 1984: p. 19). In addition, generally, to (Krautheimer, 1965), Feyerabend also refers to (Edgerton, 1975). Significantly enough, the first chapter of Edgerton’s book begins—and one can note the influence of the terminology used beyond Feyerabend—as follows: “More than five centuries ago, a diminutive Florentine artisan in his late forties conducted a modest ‘experiment’ near a doorway in a cobbled cathedral plaza.” Edgerton’s illustration (followed by a comprehensive citation from Manetti) in (Edgerton, 1975: pp. 126-127) appears in Feyerabend’s chapter on Brunelleschi, noted as “after Edgerton” (Feyerabend, 1999: p. 95). Cf. (Heelan , 1983) for other references on Alberti and perspective. ↩︎

- Albrecht Dürer, Underweysung der Messung, mit dem Zirckel und Richtscheyt, in Linien, Ebenen und ganꜩen corporen (as cited in Heelan, 1983: p. 102). ↩︎

- Thus Feyerabend observes, contra Vasari that for Renaissance theorists, the elements of perspective, natural postures, delicate colours, character, emotions—are obstacles, not improvements for an artist who wants a portrait or a statue to convey absolute power or spiritual eminence: what is permanent and independent of circumstances (Feyerabend, 1987: p. 148). ↩︎

- “Eine Diskussion der Rieglschen Kunsheorie verbunden mit dem Versuch, sie auf die Wissenschaften anzuwenden” (Feyerabend, 1984: p. 7). The theme seems to be absent from Eric Oberheim’s planned edition/translation of Feyerabend’s notes for Science as Art (Eric shared an advance copy with participants when I presented an earlier version of the current essay at a Spring 2024 Weimar colloquium on Feyerabend organized by Helmut Heit. ↩︎